2023 Sudan conflict

Article Link :

2023 Sudan conflict – Wikipedia

An armed conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), rival factions of the military government of Sudan, began on 15 April 2023, with the fighting concentrated around the capital city of Khartoum and the Darfur region. Later, a faction of the militant Sudan People’s Liberation Movement–North (SPLM-N) led by Abdelaziz al-Hilu, also fought the SAF in regions bordering South Sudan and Ethiopia.[3][4] As of 15 August 2023, between 4,000 to 10,000 people had been killed and 6,000 to 8,000 others injured,[8][11][10] while as of 15 August 2023, 3.4 million were internally displaced and more than a million others had fled the country as refugees.[12]

The conflict began with attacks by the RSF on government sites as airstrikes, artillery, and gunfire were reported across Sudan. Throughout the conflict, RSF leader Mohamed Hamdan “Hemedti” Dagalo and Sudan’s de facto leader and army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan have disputed control of government sites in Khartoum, including the general military headquarters, the Presidential Palace, Khartoum International Airport, Burhan’s official residence, and the SNBC headquarters, as well as states and towns in Darfur and Kordofan. The two sides were then joined by rebel groups who had previously fought against the two sides. Starting in June, the SPLM-N (al-Hilu) attacked army positions in the south of the country.[3][4] In July, a faction of the Sudan Liberation Movement led by Mustafa Tambour (SLM-T) officially joined the conflict in support of the SAF,[2] while in August, the rebel Tamazuj movement based in Darfur and Kordofan joined forces with the RSF.[13]

Background

Main article: History of Sudan

The history of conflicts in Sudan has consisted of foreign invasions and resistance, ethnic tensions, religious disputes, and disputes over resources.[14][15] Two civil wars between the central government and the southern regions killed 1.5 million people, and a conflict in the western region of Darfur displaced two million people and killed more than 200,000 others.[16] Since independence in 1956, Sudan has experienced more than 15 military coups[17] and it has been ruled by the military for the majority of that time, interspersed with periods of democratic parliamentary rule.[18][19]

War in Darfur and formation of the RSF

By the turn of the 21st century, Sudan’s western Darfur region had endured prolonged instability and social strife due to a combination of racial and ethnic tensions and disputes over land and water. In 2003 this erupted into a full-scale rebellion against government rule, against which president and military strongman Omar al-Bashir vowed forceful action. The resulting War in Darfur was marked by widespread state-sponsored acts of violence, leading to charges of war crimes and genocide against al-Bashir.[20] The initial phase of the conflict left approximately 300,000 dead and 2.7 million forcibly displaced; though the intensity of the violence later declined, the region remained far from peaceful.[21]

In order to crush uprisings by non-Arab tribes in the Nuba Mountains, al-Bashir relied upon the Janjaweed, a collection of Arab militias drawn from camel-trading tribes active in Darfur and portions of Chad. In 2013, al-Bashir announced that the Janjaweed would be reorganized as the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and placed under the command of Janjaweed commander Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, more commonly known as Hemedti.[22][23][24][25] The RSF perpetrated mass killings, mass rapes, pillage, torture, and destruction of villages and were accused of committing ethnic cleansing against the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa.[24] Leaders of the RSF have been indicted for genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court (ICC),[26] but Hemedti was not personally implicated in the 2003–2004 atrocities.[21] In 2017, a new law gave the RSF the status of an “independent security force”.[24] Hemedti received several gold mines in Darfur as patronage from al-Bashir, and his personal wealth grew substantially.[26][25] Bashir sent RSF forces to quash a 2013 uprising in South Darfur and deployed RSF units to fight in Yemen and Libya.[23] During this time, the RSF developed a working relationship with the Russian private military outfit Wagner Group.[27] These developments ensured that RSF forces grew into the tens of thousands and came to possess thousands of armed pickup trucks which regularly patrolled the streets of Khartoum.[27] The Bashir regime allowed the RSF and other armed groups to proliferate to prevent threats to its security from within the armed forces, a practice known as “coup-proofing“.[28]

Political transition

Main article: Sudanese transition to democracy

Chairman of the Transitional Sovereignty Council, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan.

Commander of the Rapid Support Forces, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo.

In December 2018, protests against al-Bashir’s regime began, starting the first phase of the Sudanese Revolution. Eight months of sustained civil disobedience were met with violent repression.[29] In April 2019, the military (including the RSF) ousted al-Bashir in a coup d’état, ending his three decades of rule; the army established the Transitional Military Council, a junta.[29][26][25] Bashir was imprisoned in Khartoum; he was not turned over to the ICC, which had issued warrants for his arrest on charges of war crimes.[30] Protests calling for civilian rule continued; in June 2019, the RSF perpetrated the Khartoum massacre, in which more than a hundred demonstrators were killed[29][25][23] and dozens were raped.[23] Hemedti denied orchestrating the attack.[25]

In August 2019, in response to international pressure and mediation by the African Union and Ethiopia, the military agreed to share power in an interim joint civilian-military unity government (the Transitional Sovereignty Council), headed by a civilian Prime Minister, Abdalla Hamdok, with elections which will be held in 2023.[20][29] In October 2021, the military seized power in a coup led by Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) leader Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Hemedti. The Transitional Sovereignty Council was reconstituted as a military junta led by Al-Burhan, monopolizing power[31] and halting Sudan’s transition to democracy.[30]

Origins of the SPLM-N and the SLM

The SPLM-N was founded by units of the predominantly South Sudanese Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army stationed in areas that remained in Sudan following the South Sudanese vote for independence in 2011[32] who then led a rebellion in the southern states of South Kordofan and Blue Nile a few months later. In 2017, the SPLM-N split between a faction led by Abdelaziz al-Hilu and one led by Malik Agar over ideological differences.[33] During the Sudanese Revolution, al-Hilu’s faction declared an indefinite unilateral ceasefire.[34] In 2020, a peace agreement was signed between the Sudanese government and Agar’s faction,[35] with Agar later joining the Transitional Sovereignty Council in Khartoum. Al-Hilu held out until he agreed to sign a separate peace agreement with the Sudanese government a few months after.[36] Further steps to consolidate the agreement stalled following the 2021 coup,[37] and al-Hilu’s faction subsequently engaged in clashes with the RSF. On 8 June 2023, al-Hilu’s forces, which were nominally based in the Nuba Mountains[34] began mobilizing around South Kordofan’s capital, Kadugli, moving into several army camps and prompting the SAF to reinforce its positions despite an RSF blockade.[38]

The Sudan Liberation Movement (or Army; SLM, SLA, or SLM/A) is a rebel group active in Darfur, primarily composed of members of non-Arab ethnic groups[39] and established in response to their marginalization by the Bashir regime.[40][41] Since 2006, the movement has split into several factions due to disagreements over the Darfur Peace Agreement, with some factions joining the government in Khartoum.[42][43][44]

Prelude

Tensions between the RSF and the Sudanese junta began to escalate in February 2023, as the RSF began to recruit members from across Sudan. A military buildup in Khartoum was succeeded by an agreement for de-escalation, with the RSF withdrawing its forces from the Khartoum area.[45] The junta later agreed to hand over authority to a civilian-led government,[46] and it was delayed due to renewed tensions between Burhan and Hemedti, who serve as chairman and deputy chairman of the Transitional Sovereignty Council, respectively.[30][47] Chief among their political disputes is the integration of the RSF into the military:[30][48] The RSF insisted on a 10-year timetable for its integration into the regular army, while the army demanded integration within two years.[49] Other contested issues included the status given to RSF officers in the future hierarchy, and whether RSF forces should be under the command of the army chief rather than Sudan’s commander-in-chief, who is al-Burhan.[50] They have clashed over authority over sectors of Sudan’s economy that are controlled by the two respective factions. As a sign of their rift, Hemedti expressed regret over the October 2021 coup.[31]

On 11 April 2023, RSF forces were deployed near the city of Merowe as well as in Khartoum.[51] Government forces ordered them to leave, and they refused. This led to clashes when RSF forces took control of the Soba military base south of Khartoum.[51] On 13 April, RSF forces began their mobilization, raising fears of a potential rebellion against the junta. The SAF declared the mobilization illegal.[52]

Conflict

For a chronological guide, see Timeline of the 2023 Sudan conflict.

See also: List of military engagements during the 2023 Sudan conflict

April

On 15 April 2023, the RSF attacked SAF bases across Sudan, including Khartoum and its airport.[49][53] Clashes between the two groups occurred at the Presidential Palace and at the residence of General al-Burhan.[54] In response, the SAF closed all airports and conducted airstrikes on RSF positions.[54] There were clashes at the headquarters of the state broadcaster, Sudan TV, which was later captured by RSF forces.[55] Bridges and roads in Khartoum were closed, and the RSF claimed that all roads heading south of Khartoum were closed.[56] On 16 April, the SAF announced the rescue of a major general and a brigadier, the arrests of multiple RSF officers, and the taking of Merowe Airport.[57] The Sudan Civil Aviation Authority closed the country’s airspace,[58] and telecommunications provider MTN shut down Internet services.[59] Clashes resumed on 17 April in Khartoum, Omdurman, and Merowe airport.[60] The SAF claimed control of the headquarters of Sudan TV and state radio in Khartoum,[61] and the RSF released a video on their Twitter page.[62]

In an interview with Al Jazeera, Hemedti accused Abdel Fattah al-Burhan of forcing the RSF to begin confrontations and accused SAF commanders of scheming to bring deposed leader Omar al-Bashir back to power.[63] On Twitter, Hemedti called for the international community to intervene against Burhan, claiming that the RSF was fighting against radical militants.[64]

Fighting between the warring sides continued in Khartoum. The SAF accused the RSF of assaulting civilians and carrying out acts of looting and burning.[65] Witnesses said SAF reinforcements were brought in from near the eastern border with Ethiopia. Although a ceasefire was announced, fighting continued, with explosions reported in El-Obeid.[66] The SAF regained control over Merowe airport. The RSF claimed to have repelled an SAF attack and shot down two helicopters.[67] Shelling and gunfire was reported in Khartoum, Khartoum Bahri, and Omdurman on the day of Eid al-Fitr, 21 April.[68] Fighting was described as particularly intense along the highway going to Port Sudan and in the industrial zone of al-Bagair.[69] Fighting spread along the main road leading southeast out of the capital.[70] The Chadian Army stopped and disarmed a contingent of 320 Sudanese soldiers who had entered the country from Darfur while fleeing the RSF on 17 April.[71]

On 23 April, a series of mass escapes occurred at Kobar Prison and four other prisons, with over 25,000 detainees escaping.[72][73] There was a near-total Internet outage across the country, which was attributed to electricity shortages caused by attacks on the electric grid.[74] The RSF claimed to have captured military manufacturing facilities and a power plant north of Khartoum.[75] The World Health Organization expressed concern over the National Public Health Laboratory, which had been seized by one of the warring sides on 25 April.[76] AP Moller-Maersk announced it would stop taking new bookings of goods for Sudan,[77] and intercommunal clashes were reported in Blue Nile State and in Geneina.[78][79] Fighting between the two sides continued, with artillery fire reported in Omdurman, while a 72-hour ceasefire started on 27 April.[80] On 30 April, the SAF announced it was launching an all-out attack to flush out the RSF in Khartoum using air strikes and artillery.[81] The Sudanese police deployed its Central Reserve Forces in the streets of Khartoum to maintain law and order,[82] and the unit later said that it had arrested 316 “rebels”, referring to the RSF.[83] Local authorities in Khartoum placed civil servants on open-ended leave.[84]

May

The SAF claimed to have weakened the RSF’s combat capabilities and repelled their advances in multiple regions.[85] Air strikes and fighting persisted in areas such as Omdurman, the Presidential Palace, Khartoum Bahri, and al-Jerif.[86][87] During this period, both sides made allegations against each other. The RSF claimed to have shot down a fighter jet during SAF airstrikes,[88] while the Sudanese government reported a number of injuries since the conflict began.[89] UN relief head Martin Griffiths expressed frustration at the lack of commitment from both sides to end the fighting.[90]

The situation became more complicated when the Turkish embassy in Khartoum was targeted, resulting in its relocation to Port Sudan.[91] The warring sides signed an agreement in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, to ensure the safe passage of civilians, protect relief workers, and prohibit the use of civilians as shields.[92] The agreement did not include a ceasefire, and clashes resumed in Geneina, causing more casualties.[92] The conflict drew international attention, with the United Nations Human Rights Council voting to increase monitoring of abuses.[93] UNICEF reported the destruction of a factory producing food for malnourished children.[94] The situation remained volatile, with both sides trading blame for attacks on churches,[95] hospitals,[96] and embassies.[97]

Hemedti vowed to continue fighting and expressed his desire to capture and hang Burhan after trial.[98] Burhan made a public appearance among cheering soldiers, reaffirming their presence in the conflict.[99] On 19 May, Burhan removed Hemedti as his deputy in the Transitional Sovereignty Council and replaced him with former rebel leader and council member Malik Agar.[100]

Casualties mounted, particularly in Geneina, where Arab militias loyal to the RSF were accused of atrocities against non-Arab residents.[101] A temporary ceasefire was signed and faced challenges as fighting persisted in Khartoum, and the agreed-upon ceasefire time saw further violence.[102] Between 28 and 97 people were reportedly killed by the RSF and Arab militias when they attacked the predominantly Masalit town of Misterei in West Darfur on 28 May.[103]

The Sudanese defense ministry issued a mobilisation order for army pensioners and capable individuals to join the SAF.[104] Peace talks between the warring sides were suspended due to violations of the ceasefire.[105] The conflict resulted in civilian casualties, including attacks on markets[106] and abductions.[107]

June

Khartoum witnessed tank battles resulting in casualties and injuries.[108][109] The RSF took control of the National Museum of Sudan,[110] Yarmouk munitions factory,[111] and the Police Central Reserve Forces headquarters in Khartoum,[4] adding to the instability.[112] Fighting also persisted in various regions, including Kutum, Tawila[113] and Geneina, where hundreds lost their lives and extensive destruction occurred.[114][115] Acute food insecurity affected a significant portion of Sudan’s population.[115]

In Darfur, armed militias were accused of carrying out summary executions,[113][116] exacerbating the humanitarian crisis.[117] The governor of West Darfur, Khamis Abakar, was abducted and killed by armed men hours after accusing the RSF of genocide and calling for international intervention in a TV interview.[118] The leaders of seven Arab tribes, including that of Hemedti’s, pledged their allegiance to the RSF.[119]

A faction of the militant Sudan People’s Liberation Movement–North (SPLM-N) led by Abdelaziz al-Hilu broke a long-standing ceasefire agreement and attacked SAF units in Kadugli, Kurmuk and al-Dalanj, the latter coinciding with an attack by the RSF. The SAF claimed to have repelled the attacks,[4][120] while the rebels claimed to have attacked in retaliation for the death of one of their soldiers at the hands of the SAF and vowed to free the region from “military occupation”.[34] More than 35,000 were displaced by the fighting.[34] Speculation arose as to whether the attacks were part of an unofficial alliance between al-Hilu and the RSF or an attempt by al-Hilu to strengthen his position in future negotiations concerning his group.[121] Civil society organizations supporting the SPLM-N claimed its operations sought to protect civilians from possible attacks by the RSF.[122]

Ceasefires were announced but often violated, leading to further clashes. The SAF and RSF engaged in mutual blame for incidents, while the Sudanese government took actions against international envoys.[123] The Saudi embassy in Khartoum was attacked, and evacuations from an orphanage were carried out amid the chaos.[124] The United States imposed sanctions on firms associated with the SAF and RSF, along with visa restrictions on individuals involved in the conflict.[125] Amidst the turmoil, Sudan faced diplomatic strains with Egypt, leading to challenges for Sudanese refugees seeking entry.[126][127] The International Committee of the Red Cross facilitated the release of personnel held by the RSF.[128]

Despite brief truces for the Eid al-Adha holiday, heavy fighting persisted in Khartoum.[129]

July

During July, the conflict continued. The Sudanese Doctors Union accused the RSF of attacking the Al-Shuhada Hospital in Khartoum and killing a staff member,[130] which the RSF denied.[131] In response to the escalating violence, the SAF conducted airstrikes and shelling on civilians[132][133][134] and positions held by the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N).[135] In South Kordofan, the SPLM-N (al-Hilu) gained control of several SAF bases,[136][135][137] while the RSF clashed with a coalition of armed groups in El-Fashir.[135][138] A faction of the Sudan Liberation Movement led by Mustafa Tambour (SLM-T) joined the conflict in support of the SAF in Darfur.[2]

The RSF was accused of looting and occupying homes in Khartoum and of continued ethnic cleansing in Geneina.[139] The Combating Violence Against Women Unit stated that it had recorded 88 cases of sexual assault in Geneina, Khartoum, and Nyala.[140] On 13 July, the UN announced the discovery of 87 bodies, including that of ethnic Masalits, buried in a mass grave in Darfur. According to the UN Human Rights Office, the deceased were killed by the RSF and their allied militia and buried on 20-21 June 2023. United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Volker Türk, demanded a “prompt, thorough and independent investigation”.[141] The UN warned that Sudan was on the brink of another civil war.[142] On 22 July it was reported that 10,000 people had died since the start of the conflict in West Darfur alone.[10] The RSF and Arab militias were said to have killed lawyers, human rights monitors, doctors and non-Arab tribal leaders,[143][144] and committed robberies and sexual violence.[145]

In response to the violence, the United Kingdom imposed sanctions on firms linked to the SAF and RSF for their involvement in funding and providing weapons, seeking to curtail their actions.[146] Despite regional efforts for mediation and resolution,[147] the conflict persisted, and the SAF’s boycott of a crucial meeting hindered the peace process.[148]

Internal divisions within Sudanese tribes[149] and the SAF further complicated the situation,[150] with some pledging their support to the RSF.[151] Notably, RSF leader Hemedti made his first video announcement since April, reiterating his willingness to negotiate if Burhan and the rest of the SAF’s leadership were removed from power.[152]

August

The RSF claimed that it had taken full control over all of Central Darfur state.[153]

The Third Front, known as Tamazuj, one of several groups based in Darfur and Kordofan that signed a peace agreement with the Sudanese government in 2020 and had been sidelined over its alleged links with Sudanese military intelligence, formally declared its alliance with the RSF. Several of its commanders had previously supported the RSF at the start of the conflict.[13]

Casualties

As of 15 August, more than 4,000 people had been killed and 6,000 others injured, according to the Sudanese Health Ministry and the UN.[8][9] The Sultanate of Dar Masalit claimed on 20 June that more than 5,000 people were killed and about 8,000 were wounded in fighting in West Darfur alone,[11] while a Masalit tribal leader told the Sudanese news outlet Ayin Network on 22 July that more than 10,000 people had been killed in the state.[10] On 12 June, the Sudan Doctors Syndicate said at least 959 civilians had been killed and 4,750 others were injured.[154] On 15 August, the UN said that at least 435 children had been killed in the conflict.[8] Doctors on the ground warned that stated figures do not include all casualties as people could not reach hospitals due to difficulties in movement.[155] A spokesperson for the Sudanese Red Crescent was quoted as saying that the number of casualties “was not small”.[63] Sudanese prosecutors recorded over 500 missing persons cases across the country, some of which were enforced disappearances, and were mostly blamed on the RSF.[156]

Notable deaths

Asia Abdelmajid, an actress, was killed in a crossfire in Khartoum Bahri.[157] A singer, Shaden Gardood, was killed in a crossfire in Omdurman, as was former football player Fozi el-Mardi and his daughter.[158] The governor of West Darfur, Khamis Abakar, was abducted and killed by armed men hours after accusing the RSF of genocide and calling for international intervention in a TV interview.[118]

Darfur

At least 25 civilians were killed and 26 injured during initial clashes in North Darfur, and an additional three civilians were killed by a rocket-propelled grenade.[159] A representative of Médecins Sans Frontières said at least 279 wounded people were admitted to the only functioning hospital in the state capital al-Fashir, of whom 44 died.[160] In Geneina, West Darfur, ethnic clashes that began in the last week of April had killed at least 1,100 people,[161] while the Sultanate of Dar Masalit claimed that more than 5,000 people were killed and about 8,000 were wounded in the city.[11] In July, a Masalit tribal leader claimed that more than 10,000 people had been killed in West Darfur alone, and that 80% of Geneina’s residents had fled.[10]

Massacres were recorded in towns such as Tawila[162] and Misterei,[103] while a mass grave was discovered in Geneina containing the bodies of 87 people killed in clashes.[141] Several intellectuals, politicians, professionals and nobility were assassinated. Most of these atrocities were blamed on the RSF and allied Arab militias. Witnesses and other observers described the violence in the region as tantamount to ethnic cleansing or even genocide, with non-Arab groups such as the Masalit being the primary victims.[162] Mujeebelrahman Yagoub, Assistant Commissioner for Refugees in West Darfur called the violence worse than the War in Darfur in 2003 and the Rwandan genocide in 1994.[163]

Foreign casualties

15 Syrians,[164] 15 Ethiopians[165] and 9 Eritreans[166] were killed across the country. An Indian national working in Khartoum died after being hit by a stray bullet on 15 April.[167] Two Americans were killed, including a professor working in the University of Khartoum who was stabbed to death while evacuating.[168][169] A two-year-old girl from Turkey was killed while her parents were injured after their house was struck by a rocket on 18 April.[170] Two Egyptian doctors were killed in their home in Khartoum and had their possessions stolen on 13 June.[171] Ten students from the Democratic Republic of Congo were killed in an SAF airstrike on the International University of Africa in Khartoum on 4 June.[172] The SAF claimed that the Egyptian assistant military attaché was killed by RSF fire while driving his car in Khartoum, which was refuted by the Egyptian ambassador.[173]

Two Greek nationals trapped in a church on 15 April sustained leg injuries when caught in crossfire while trying to leave.[174][175] A Filipino migrant worker[176] and an Indonesian student at a school in Khartoum were injured by stray bullets.[177] On 17 April, the European Union Ambassador to Sudan, Aidan O’Hara of Ireland, was assaulted by unidentified “armed men wearing military fatigues” in his home, he suffered minor injuries and was able to resume working on 19 April.[178][179] On 23 April, a French evacuation convoy was shot at, injuring one person.[180] The French government later confirmed the casualty to be a French soldier.[181] An employee of the Egyptian embassy was shot and injured during an evacuation mission.[182][183]

Casualties among humanitarian workers

In the Battle of Kabkabiya, three employees of the World Food Programme (WFP) were killed after being caught in the crossfire at a military base. Two other staff members were injured.[54] On 18 April, the EU’s top humanitarian aid officer in Sudan, Wim Fransen of Belgium, was shot and injured in Khartoum.[184] On 21 April, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported that one of its local employees was killed in a crossfire while travelling with his family near El-Obeid.[185] On 20 July, an 18-member team of Médecins Sans Frontières was attacked while transporting supplies to the Turkish Hospital in south Khartoum. By then, the World Health Organization had verified 51 attacks on medical facilities and personnel since the conflict began, resulting in 10 deaths and 24 injuries.[186] On 25 July, Humanitarian Coordinator Clementine Nkweta-Salami said 18 aid workers had been killed and over two dozen others were detained or unaccounted for.[187]

The situation has been further compounded by attacks on humanitarian facilities, with more than 50 warehouses looted, 82 offices ransacked, and over 200 vehicles stolen. One particularly devastating looting incident in El Obeid in early June resulted in the loss of food “that could have fed 4.4 million people”.

Attacks on journalists

Media organizations accused both the SAF and the RSF of threatening, attacking and even killing several journalists during the conflict, with the Sudanese Journalists Syndicate documenting more than 40 such violations during the second half of May alone.[188] Aside from the occupation of state media channels, the RSF raided the offices of the newspapers El Hirak El Siyasi, El Madaniya and the Sudanese Communist Party‘s El Midan[189] and shot and injured photojournalists Faiz Abubakr,[190] and Ali Shata,[191] while the SAF was accused of circulating lists of journalists it accused of supporting the RSF.[192]

BBC journalist Mohamed Othman was reportedly attacked and beaten in Khartoum while a correspondent and cameramen for the El Sharg news outlet were detained for hours near Merowe airport on the first day of the fighting on 15 April. On 16 June, Al Jazeera journalists Osama Sayed Ahmed and Ahmed El Buseili were shot by snipers in Khartoum,[193] while the RSF detained two of the channel’s other reporters, Ahmed Fadl and Rashid Gibril, in Khartoum on 16 May, and subsequently looted Fadl’s residence. During a live report on 29 April, al-Arabiya correspondent Salem Mahmoud was interrupted and questioned by the RSF.[194] On 30 June, Radio Zalingei journalist Samaher Abdelshafee was killed by shelling at Hasaheisa refugee camp near Zalingei, where she and her family had fled after fighting in the city.[195] Sudan TV photographer Esam Marajan was shot dead inside his home in the Beit El Mal neighborhood of Omdurman in the first week of August.[196]

The Sudanese Journalists Syndicate (SJS) reported on 10 August that 13 newspapers had ceased operations due to the conflict, while FM radio stations and channels also halted broadcasts, with journalists grappling with unpaid wages.[197]

Sexual violence

In July, authorities reported at least 88 cases of sexual assault on women across the country, most of them blamed on the RSF.[198] NGOs estimated that the figure could possibly reach 4,400.[199]

Foreign involvement

Libya

On 18 April, an SAF general claimed that two unnamed neighboring countries were trying to provide aid to the RSF.[200] According to The Wall Street Journal, Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar, who is backed by United Arab Emirates and the Russian paramilitary Wagner Group, dispatched at least one plane to fly military supplies to the RSF.[201][when?] The Observer reported that Haftar assisted in preparing the RSF for months before the conflict broke out.[202] The Libyan National Army, which is commanded by Haftar, denied providing support to any warring groups in Sudan and said it was ready to play a mediating role.[203]

Wagner Group

Prior to the conflict, the UAE and the Wagner Group were involved in business deals with the RSF.[204][205][better source needed] According to CNN, Wagner supplied surface-to-air missiles to the RSF, picking up the items from Syria and delivering some of them by plane to Haftar-controlled bases in Libya to be then delivered to the RSF, while dropping other items directly to RSF positions in northwestern Sudan.[206] American officials said that Wagner was offering to supply additional weapons to the RSF from its existing stocks in the Central African Republic.[207]

In response to these allegations, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov defended the possible involvement of the Wagner Group, saying that Sudan had the right to use its services.[208] The head of the Wagner Group, Yevgeny Prigozhin, denied supporting the RSF, saying that the company has not had a presence in Sudan for more than two years.[209] The RSF denied allegations that Wagner Group was supporting them, instead stating that the SAF was seeking such support.[210][211] Sudan has denied the presence of Wagner on its territory.[212][213]

UAE

A report published by the Wall Street Journal on 10 August quoted Ugandan officials as saying that an Emirati plane on a stopover at Entebbe Airport en route to Amdjarass International Airport in eastern Chad turned out upon inspection to have been carrying dozens of green plastic crates in the plane’s cargo hold filled with ammunition, assault rifles and other small arms”, rather than food and other aid officially listed on the aircraft’s manifest supposedly meant for Sudanese refugees. Despite the discovery, the plane was allowed to take off, and the officials said they received orders from their superiors not to inspect any more planes from the UAE. Prior to this, the UAE had long been accused of supporting the RSF. The UAE Foreign Ministry subsequently denied the allegations, saying that the country “does not take sides” in the conflict.[214]

Chad

On 7 June, Hissein Alamine Tchaw-tchaw, a Chadian dissident who belongs to the same ethnic group as Hemedti and claiming to be the leader of the Movement for the Fight of the Oppressed in Chad (MFOC), which is fighting the government of President Mahamat Déby, posted a video showing his participation in an RSF attack on the Yarmouk munitions factory in Khartoum.[215]

Egypt

On 16 April, the RSF claimed that its troops in Port Sudan were attacked by foreign aircraft and issued a warning against any foreign interference.[216] According to former CIA analyst Cameron Hudson, Egyptian fighter jets were a part of these bombing campaigns against the RSF, and Egyptian special forces units have been deployed and are providing intelligence and tactical support to the SAF.[217] The Wall Street Journal said that Egypt had sent fighter jets and pilots to support the Sudanese military.[201] On 17 April, satellite imagery obtained by The War Zone revealed that one Egyptian Air Force MiG-29M2 fighter jet had been destroyed and two others had been damaged or destroyed at Merowe Airbase. A Sudanese Air Force Guizhou JL-9 was among the destroyed aircraft.[218] After initial confusion, the RSF accepted the explanation that Egyptian combat and support personnel were conducting exercises with the Sudanese military prior to the outbreak of hostilities.[49]

Egyptian POWs

On 15 April, RSF forces claimed, via Twitter, to have taken Egyptian troops prisoner near Merowe,[219][220] and a military plane carrying markings of the Egyptian Air Force.[221] Initially, no official explanation was given for the Egyptian soldiers’ presence, while Egypt and Sudan have had military cooperation due to diplomatic tensions with Ethiopia.[222] Later on, the Egyptian Armed Forces stated that around 200 of its soldiers were in Sudan to conduct exercises with the Sudanese military.[49] Around that time, the SAF reportedly encircled RSF forces in Merowe airbase. As a result, the Egyptian Armed Forces announced that it was following the situation as a precaution for the safety of its personnel.[63][223][better source needed] The RSF later stated that it would cooperate in repatriating the soldiers to Egypt.[221] On 19 April, the RSF stated that it had moved the soldiers to Khartoum and would hand them over when the “appropriate opportunity” arose.[224] 177 of the captured Egyptian troops were released and flown back to Egypt aboard three Egyptian military planes that took off from Khartoum airport later in the day. The remaining 27 soldiers, who were from the Egyptian Air Force, were sheltered at the Egyptian embassy and later evacuated.[225][226]

Ethiopia

On 19 April, the Sudanese newspaper Al-Sudani reported that the SAF had repelled an invasion by the Ethiopian Armed Forces in the disputed Al Fushqa District and that the SAF had inflicted heavy losses on Ethiopian personnel and equipment.[227] Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed denied that clashes had occurred, blaming agitators for the reports.[228][229] Abdul Qadir Al-Haymi, a journalist at Al-Sudani, expressed his regret for publishing the story about the Ethiopian incursion, emphasizing that the story was not true and that no clashes had occurred between Sudanese and Ethiopian forces.[230]

Kenya

The SAF rejected Kenya’s involvement in mediation efforts to end the conflict in July after General Burhan accused President William Ruto of having a business relationship with Hemedti[231] and providing a haven to the RSF in the country.[232] In response to proposals for a peacekeeping force composed by African countries to be deployed in Sudan made in an IGAD committee chaired by Ruto, the SAF’s Assistant Commander-in-Chief Lieutenant General Yasir Alatta accused Ruto of being a mercenary of another country, whom he did not identify, and dared Ruto to deploy the Kenyan army and that of his alleged backer.[233]

In response, Kenyan Foreign Secretary Abraham Korir Sing’oei subsequently called these allegations “baseless”,[234] while the Foreign Ministry released a statement insisting on the country’s neutrality in the conflict.[235]

A hacking group calling itself Anonymous Sudan launched cyberattacks on Kenyan government and private websites in the last week of July.[236]

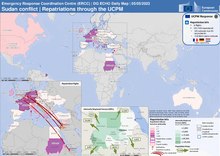

Evacuation of foreign nationals

Main article: Evacuation of foreign nationals during the 2023 Sudan conflict

The outbreak of violence has led foreign governments to monitor the situation in Sudan and move towards the evacuation and repatriation of its nationals. Among some countries with a number of expatriates in Sudan are Egypt, which has more than 10,000 citizens in the country,[237] and the United States, which has more than 16,000 citizens, most of whom are dual nationals.[238] Efforts at extraction were hampered by the fighting within the capital Khartoum, particularly in and around the airport. This has forced evacuations to be undertaken by road via Port Sudan on the Red Sea, which lies about 650 km (400 miles) northeast of Khartoum.[239] from where they were airlifted or ferried directly to their home countries or to third ones. Other evacuations were undertaken through overland border crossings or airlifts from diplomatic missions and other designated locations with direct involvement of the militaries of some home countries. Some transit hubs used during the evacuation include the port of Jeddah in Saudi Arabia and Djibouti, which hosts military bases of the United States, China, Japan, France, and other European countries.[240]

Humanitarian impact

Main article: Humanitarian impact of the 2023 Sudan conflict

The humanitarian crisis following the fighting was further exacerbated by the violence occurring during a period of high temperatures, drought and it starting during the fasting month of Ramadan. Civilians were unable to venture outside of their homes to obtain food and supplies for fear of getting caught in the crossfire. A doctors’ group said that hospitals remained understaffed and were running low on supplies as wounded people streamed in.[241] The World Health Organization recorded around 26 attacks on healthcare facilities, some of which resulted in casualties among medical workers and civilians.[242] The Sudanese Doctors’ Union said more than two-thirds of hospitals in conflict areas were out of service with 32 forcibly evacuated by soldiers or caught in the crossfire.[243] This included about half of Khartoum’s 130 medical facilities and all hospitals in West Darfur.[9] Outbreaks of diseases such as measles, cholera and diarrhea were reported across the country.[244]

The United Nations reported that shortages of basic goods, such as food, water, medicines and fuel have become “extremely acute”.[245] The delivery of badly-needed remittances from overseas migrant workers was also halted after Western Union announced it was closing all operations in Sudan until further notice.[246] The World Food Programme said that more than $13 million worth of food aid destined for Sudan had been looted since the fighting broke out.[247] An estimated 25 million people, equivalent to more than half of Sudan’s population, were said to be in need of aid.[248] In particular, the looting of the WFP’s warehouses in El-Obeid on 1 June led to the loss of food aid meant to feed 4.4 million people.[249] On 25 July, Humanitarian Coordinator Clementine Nkweta-Salami said attacks on humanitarian facilities had led to more than 50 warehouses looted, 82 offices ransacked, and over 200 vehicles stolen.[187]

In July, Sudanese economists estimated the total amount of damage brought by the conflict at $9 billion, or an average of $100 million per day, while the value of property and goods looted was estimated at another $40 billion, with the most affected areas being Khartoum and South Darfur.[250]

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs said on 24 July that over 40,000 children had lost access to education after being displaced.[251]

Refugees

Main article: 2023 Sudanese refugee crisis

The International Organization for Migration said in August that the fighting in Sudan had produced 3.4 million internally displaced persons, while more than a million had fled the country altogether.[12] The International Organization for Migration estimated that around 65% of IDPs had come from the Khartoum region.[252] Of those, who fled abroad, more than 160,000 of them were Masalit who fled to Chad to escape ethnically-based attacks by the RSF and allied militias.[253] Fighting between the SAF and the SPLM-N (al-Hilu) had reportedly displaced more then 35,000 people in Blue Nile State alone, with 3,000 of them fleeing to Ethiopia.[34] As of August, more than 400,000 people had fled to Chad, making it the largest single destination of refugees from the conflict.[12]

Criticism was levelled at diplomatic missions operating in Sudan for their slow response in helping Sudanese visa applicants whose passports were left behind in embassies following their closure during evacuation efforts, preventing them from leaving the country.[254]

Peace efforts

April

On 16 April, representatives from the SAF and the RSF agreed to a proposal by the United Nations to pause fighting between 16:00 and 19:00 local time (CAT).[255] The SAF announced that it approved a UN proposal to open a safe passage for urgent humanitarian cases for 3 hours every day starting from 16:00 local time, and stated that it reserved the right to react if the RSF “commit[ted] any violations”.[256] Gunfire and explosives continued to be heard during the ceasefire, drawing condemnation from Special Representative Volker Perthes.[257]

On 17 April, the governments of Kenya, South Sudan, and Djibouti expressed their willingness to send their presidents to Sudan to act as mediators. Khartoum Airport was closed due to fighting.[258]

On 18 April, Hemedti said the RSF agreed to a day-long armistice to allow the safe passage of civilians, including those wounded. In a tweet, he said that the decision was reached following a conversation with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken “and outreach by other friendly nations”.[259] An army general later confirmed that the SAF had agreed to a 24-hour ceasefire to start at 18:00 local time (16:00 UTC). After the start of the promised ceasefire, gunfire and shelling continued to be heard in the center of Khartoum.[260] The SAF and the RSF issued statements accusing each other of failing to respect the ceasefire. The SAF’s high command said it would continue operations to secure the capital and other regions.[261]

On 19 April, the SAF and the RSF said that they had agreed to another 24-hour ceasefire starting at 18:00 local time (16:00 GMT).[262] Fighting continued between the two sides after the ceasefire had supposedly begun.[263]

On 21 April, the RSF said it would observe a 72-hour ceasefire which would come into effect at 6:00 (4:00 GMT) that day, the beginning of the Islamic holiday of Eid ul-Fitr.[264] Despite the SAF agreeing to the truce later that afternoon, fighting continued throughout the day in Khartoum and other conflict zones.[265][266] A 72-hour ceasefire agreement was announced on 24 April,[267] and fighting continued.[268]

On 26 April, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) proposed a 72-hour extension of the ceasefire, while South Sudan offered to host mediation efforts. The SAF said it supported the plan and would send an envoy to the South Sudanese capital Juba, to participate in the talks.[269] The RSF announced its support for the extended ceasefire on 27 April.[270] Fighting continued after the start of the extended ceasefire.[271]

On 30 April, the RSF announced that the ceasefire was to be further extended by 72 hours,[272] to which the SAF later agreed.[273] Fighting continued during this ceasefire.[274]

May

On 1 May, United Nations Special Envoy to Sudan Volker Perthes announced that the SAF and the RSF had agreed to send representatives for negotiations mediated by UN, and did not give a date or venue for the talks.[275]

On 2 May, South Sudan’s Foreign Ministry said that the SAF and the RSF had agreed “in principle” to a week long ceasefire to start from 4 May,[276] only for it to break down again.[277] The Sudanese resistance committees stated that the proposed negotiations between the SAF and the RSF ignored “the only one affected by this war, the Sudanese people”, and that the negotiations were aimed at the SAF and the RSF “gain[ing] popular and political support”.[278]

On 6 May, delegates from the SAF and the RSF met directly for the first time in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia for what was described by the Saudis and the United States as “pre-negotiation talks”.[279][280] Jonathan Hutson of the Satellite Sentinel Project stated that a broad range of Sudanese civil society, “political parties, resistance committees, women’s organisations, trade unions and human rights defenders”, objected to both Burhan and Hemedti, seeing them as illegitimate leaders and insisted on participating in peace negotiations. The civil society activists called for paramilitary forces to be merged into the SAF under civilian authority.[278]

On 12 May, the SAF and the RSF signed an agreement to allow safe passage for people leaving battle zones, protect relief workers and not to use civilians as human shields; there was no ceasefire agreement.[281]

On 20 May, the SAF and the RSF agreed to a week long ceasefire starting at 21:45 local time (19:45 GMT) on 22 May, following talks in Jeddah.[282] It was later extended until 3 June.[283] But on 31 May, the SAF suspended negotiations, accusing the RSF of a lack of commitment on implementing the existing ceasefire agreement and violating its terms.[284]

June

A 24-hour ceasefire was declared and implemented on 10–11 June,[285] while a 72-hour ceasefire was declared and implemented on 18 June.[286]

On 27 June, the RSF announced a unilateral two-day ceasefire for the Eid ul-Adha holiday. Later that same day, the SAF announced its own unilateral ceasefire for the holiday.[287]

July

After the SPLM-N joined the conflict, South Sudanese President Salva Kiir said on 4 July that persuaded the faction’s leader Abdelaziz al-Hilu to stop the attacks on the SAF.[288] It continued fighting with the SAF in the succeeding days, prompting Kiir to hold talks again with its leaders on 20 July.[289]

On 10 July, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), a regional bloc composed of eight East African states, opened a summit in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia to explore options to end the conflict. In a statement, the bloc said it had agreed to request a summit of another regional body, the Eastern Africa Standby Force, to consider the latter’s possible deployment “to protect civilians and guarantee humanitarian access”. The SAF boycotted the meeting after it rejected Kenyan President William Ruto as head of the committee facilitating the talks and accused Kenya of harboring the RSF.[290] The Sudanese Foreign Ministry rejected the proposals for foreign intervention and took offense with Ethiopia and Kenya’s claims that Sudan was suffering from a power vacuum.[232]

On 13 July, Egypt hosted a summit in Cairo, wherein the SAF, the RSF and leaders of Sudan’s neighboring states agreed to a new initiative to resolve the conflict. Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi said the initiative would include establishing a lasting cease-fire, creating safe humanitarian corridors for aid delivery, and building a dialogue framework that would include all political parties and figures in the country. He also urged the warring sides to commit to peace negotiations led by the African Union.[291]

On 15 July, the SAF returned to negotiations with the RSF in Jeddah,[292] but left again on 27 July, accusing the RSF of more ceasefire violations and demanding its withdrawal from Khartoum before talks could resume.[293]

In his first video announcement since the conflict began, Hemedti said he was willing to come to a peace agreement within 72 hours if the entire SAF leadership, which he called “corrupt”, were to be removed.[152]

August

On 2 August, the SAF spokesperson, Nabil Abdallah, denied reports of an imminent ceasefire between the army and the RSF in Jeddah, stating that negotiations had stalled.[294]

Sanctions

United States

The repeated violations of the ceasefire agreements and other atrocities during the conflict led to U.S. President Joe Biden issuing an executive order on 4 May 2023 authorizing sanctions for those deemed responsible for destabilizing Sudan, undermining the democratic transition and committing human rights abuses.[295] On 1 June, the U.S. government imposed its first sanctions related to the conflict, targeting two firms associated with the SAF and two others linked to the RSF. It also imposed visa restrictions against individuals involved in the violence, but did not divulge any names.[296]

United Kingdom

On 12 July, the United Kingdom announced sanctions on firms linked to the SAF and the RSF for providing funds and weapons in the conflict.[297]

War crime investigations

On 13 July 2023, the office of the International Criminal Court‘s Chief Prosecutor Karim Ahmad Khan said it had launched an investigation into possible war crimes and crimes against humanity committed during the course of the conflict. It is limited to Darfur due to regulations stipulated by a UN Security Council resolution made in 2005.[298]

On 3 August, Amnesty International released its report on the conflict. Titled Death Came To Our Home: War Crimes and Civilian Suffering In Sudan, it documented “mass civilian casualties in both deliberate and indiscriminate attacks” by both the SAF and the RSF, particularly in Khartoum and West Darfur. It also detailed sexual violence against women and girls as young as 12, targeted attacks on civilian facilities such as hospitals and churches, and looting.[299]

On 4 August, General Burhan, as chair of the Transitional Sovereignty Council, established a committee tasked with investigating war crimes, human rights violations, and other crimes attributed to the RSF. The committee was to be chaired by a representative of the Attorney General, and also included officials from the Foreign and Justice Ministries, the SAF, the Police, the General Intelligence Service, and the National Commission for Human Rights.[300]

Disinformation

During the conflict, several instances of disinformation were observed, which aimed to manipulate public opinion, spread false narratives, and create confusion. Both the SAF and the RSF engaged in disinformation campaigns on social media platforms.[301] The RSF heavily relied on tweets and inauthentic behavior to spread its agenda and influence local and international opinions. On the other hand, the Sudanese army used Twitter to refute RSF claims and boost army morale with false victory claims.[301] The RSF had dedicated teams based in Khartoum and Dubai to engage in a digital propaganda war. They used social media, including officially verified Facebook and Twitter accounts, to showcase their activities and spread disinformation.[302]

Various misleading videos were shared on social media platforms, falsely depicting scenes of violence in the ongoing fighting between the Sudanese army and the Rapid Support Forces. Some videos were taken from other conflicts or events, misattributed to the current crisis in Sudan.[303] Some viral images on social media were unrelated or misleadingly attributed to the ongoing fighting in Sudan.[304]

Examples

On 14 April, the official SAF social media page published a video which it said was of operations carried out by the Sudanese Air Force against the RSF. Al Jazeera’s monitoring and verification unit claimed the video had been fabricated using footage from the video game Arma 3 that was published on TikTok in March 2023. The unit claimed the video showing Sudanese army commander Abdel Fattah al-Burhan inspecting the Armoured Corps, in Al-Shajara, was from before the fighting. A video reportedly of helicopters flying over Khartoum to participate in operations by the SAF against the RSF, which circulated on social media, turned out to be from November 2022.[305]

Two photos circulated on social media that depicted a burning bridge reported as Bahri bridge and a bombed building allegedly in Khartoum, were both revealed to be from the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[306][better source needed]

In April, a video supposedly showing the RSF in control of Khartoum International Airport on 15 April circulated on social media. The fact-checking website Lead Stories found that the video had appeared online 3 months prior to the conflict.[307] A video posted in June and taken by an RSF soldier showing purported victims of the Bashir regime turned out to have been that of mummies and human remains used as props from the M. Bolheim Bioarchaeology Laboratory in Khartoum, which were thought to date from 3300–3000 BCE.[308]

On 5 May, the British newspaper I reported that the RSF had sent “special bulletins” to UK politicians, which it claimed were to combat “the disproportionate amount of disinformation” about the conflict. The bulletins were created with the assistance of Capital Tap Holdings, a Dubai-based investment firm which has mining interests in Sudan. The I reported that the RSF’s Facebook page was being run jointly from UAE and Sudan, and its Instagram account appeared to be based in Saudi Arabia, with the RSF saying its media team was based in Khartoum.[309]

In June, a picture of Hemedti hospitalised in Nairobi, Kenya, was circulated in the social media and reported by Turkish Anadolu Agency.[310] Fatabyyano and Juhainah, new websites, checked the images and found it to be fabricated with the original image belongs to Elijah McCalin who was killed in Colorado in 2019.[311][310] Also in June, dominant social media account holders supporting the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) attacked the Sudanese Doctors Syndicate, accusing the organization of being partial towards the RSF and collaborating with the so-called “Janjaweed” militia. These false accusations endangered the reputation and safety of the medical professionals.[312]

Responses

On 11 August, Facebook shut down the main pages of the RSF due to a violation of its policy, “Dangerous Organizations and Individuals”. In an alternate account, the RSF accused the SAF of lodging complaints based on false reports that led to the removal of its pages and said it was in contact with Facebook’s parent company Meta Platforms to restore them.[313]

Kyle Walter of Logically, a British disinformation analysis firm, said in May: “What’s most concerning from this latest example of potential foreign interference is that it provides a look into how the nature of these threats are evolving, particularly in the context of the rapid onset of generative AI being used to create fake images and text. Although we don’t know if this so-called sophisticated ‘special bulletin’ was created by this technology, it is symbolic of the wider issue at hand: an inability to trust what you’re seeing, reading, and the undermining of the entire information landscape.”[309]

Reactions

Domestic

Former Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok publicly appealed to both al-Burhan and Hemedti to cease fighting.[314]

On 18 April, el-Wasig el-Bereir of the National Umma Party said he was in communication with the SAF and the RSF to get them to stop fighting immediately,[315] while el-Fateh Hussein of the Khartoum resistance committees called for the fighting to stop immediately, stating that the resistance committees had long called for the SAF to “return to their barracks” and for the RSF to be dissolved.[315]

Sudanese resistance committees coordinated medical support networks, sprayed antiwar messages on walls, and encouraged local communities to avoid siding with either the RSF or the SAF. Hamid Murtada, a member of the resistance committees, described the resistance committees as having “an important role in raising awareness to their constituencies and in supporting initiatives that [would] end the war immediately”.[316]

On 22 and 23 April, protests against the conflict were held by residents in Khartoum Bahri, Arbaji, and Damazin.[317] On 30 July, different groups in Kadugli organized marches against the violence in South Kordofan, some of whom supported the SAF, while others condemned the SAF, the RSF and the SPLM-N (al-Hilu).[318]

On 25 July, following a meeting in Cairo, four Sudanese political groupings, namely the Forces for Freedom and Change, the National Movement Forces, the National Accord Forces, and the National Forces Alliance, called on Burhan to form “a caretaker government” as soon as possible to rule the country during the war and promote dialogue.[319]

On 30 July, nurses of the Port Sudan Teaching Hospital Emergency Department went on strike in protest over the non-payment of salaries since the beginning of the conflict, forcing the closure of the hospital since then after other departments joined.[320]

In response to calls by SPLM-N faction leader and Transitional Sovereignty Council Deputy Chair Malik Agar to support the SAF, the Sudanese Communist Party called on upon “the tribes and people of Sudan to resist calls for recruiting their youth to favour either of the warring parties” in a statement released on 6 August. Other political groups such as the Forces for Freedom and Change-Central Council and the Sudan Revolutionary Front also expressed their rejection of the conflict and said on 7 August that they had positioned themselves “equidistant” from both the SAF and the RSF.[321]

International

On 19 April, diplomatic missions in Sudan, which included those of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union, issued a joint statement calling for fighting parties to observe their obligations under international law, specifically urging them to “protect civilians, diplomats and humanitarian actors,” avoid further escalations and initiate talks to “resolve outstanding issues”.[322]

Many countries condemned the violence and called on the warring sides to cease fighting and resume the democratic transition,[323][324][325] while Egypt, South Sudan and Israel offered to mediate between the SAF and the RSF.[326][327] Several of Sudan’s neighbors, including Chad, Egypt and South Sudan closed their border with Sudan,[49][328][329] while Eritrea said it would not establish refugee camps for those crossing its border from Sudan.[330]

International organizations also echoed demands for an end to the fighting and the restoration of civilian government.[331][332][333]